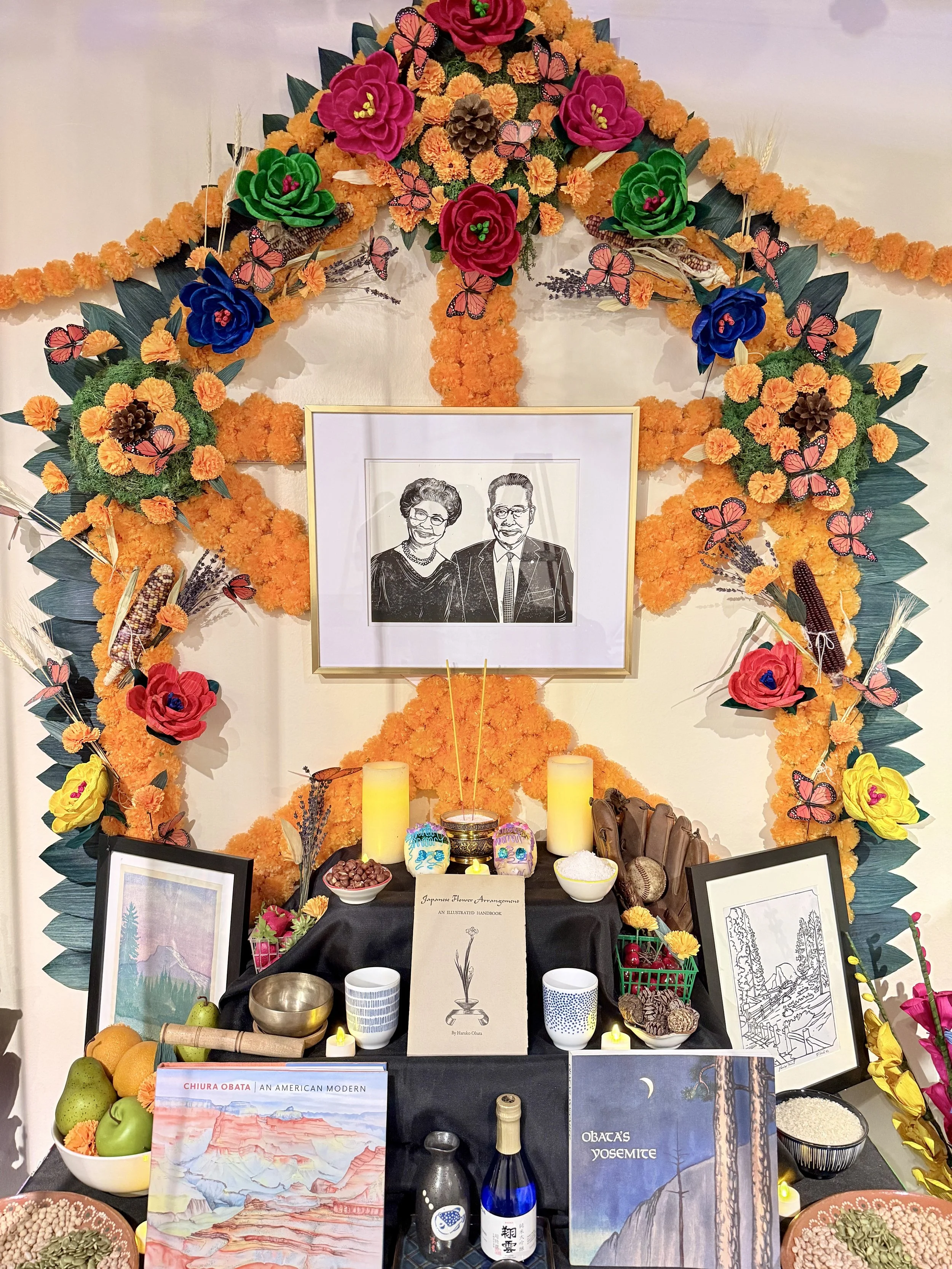

The Obata Ofrenda

Chiura & Haruko Obata

When I was approached by the California Museum about this project honoring a prominent Californian and exploring a theme on immigration, I immediately knew who I would dedicate this Ofrenda to. While all immigrant stories share a common thread, no two are identical; each reflects unique dreams, hopes, and sacrifices. I could have drawn solely from my own experience, but I chose instead to honor someone who has had a profound influence on my philosophy as an artist: Chiura Obata and his wife, Haruko.

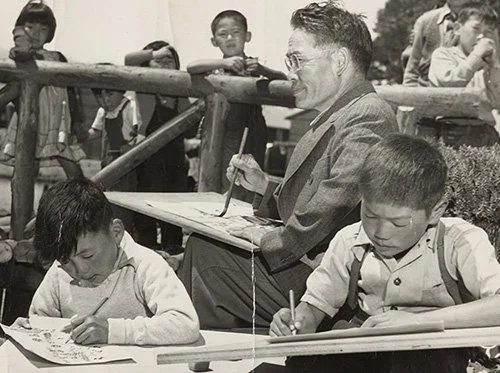

The Obatas were prominent American artists of Japanese heritage who immigrated to the United States in the early 1900s. Their story of resilience and determination to create art, even through the darkest times, stands as a powerful testament to the strength and grit often found in immigrants seeking a better life for themselves and their families. Despite being longtime U.S. residents and valued members of society: Chiura as an art professor at UC Berkeley and Haruko as an award-winning Ikebana master they were forcibly relocated during World War II under the Enemy Alien Act and imprisoned in internment camps.

After the war, it would have been natural for them to turn away from a country that had treated them so unjustly. Instead, they chose to become a bridge between nations through their art—sharing Japanese culture with Americans who visited Japan, and introducing Japanese art and traditions to audiences in the United States. Obata’s story is one of thousands that bear witness to the injustices suffered by American citizens during that era, serving as a warning to future generations.

What I did not anticipate was how deeply history would continue to echo in our present day a realization that only strengthened my decision to dedicate this altar to the Obatas.

Although I am not related to the Obatas, my involvement with Chiura Obata’s work over the past four years through collaborations on the Obata Art Weekend with the Yosemite Conservancy and Yosemite National Park has led me down a path of deep personal reflection, both as an artist and as a person. Through his art and writings, I have learned not only about technique and material diversity but also about the mindset that fuels real artistic growth.

Obata’s philosophy of “Great Nature”, the belief that art should flow from a profound harmony between the artist and the natural world, has had a lasting impact on me. It reminds me that to create is to be in conversation with nature, to listen as much as to express. Though I never had the privilege of studying under Mr. Obata himself, studying his work and words has allowed me to learn from him. Above all, his love for Yosemite and California, his perseverance, and his unwavering dedication to making art have inspired me to push harder, stay curious, and continue stepping beyond my comfort zone.

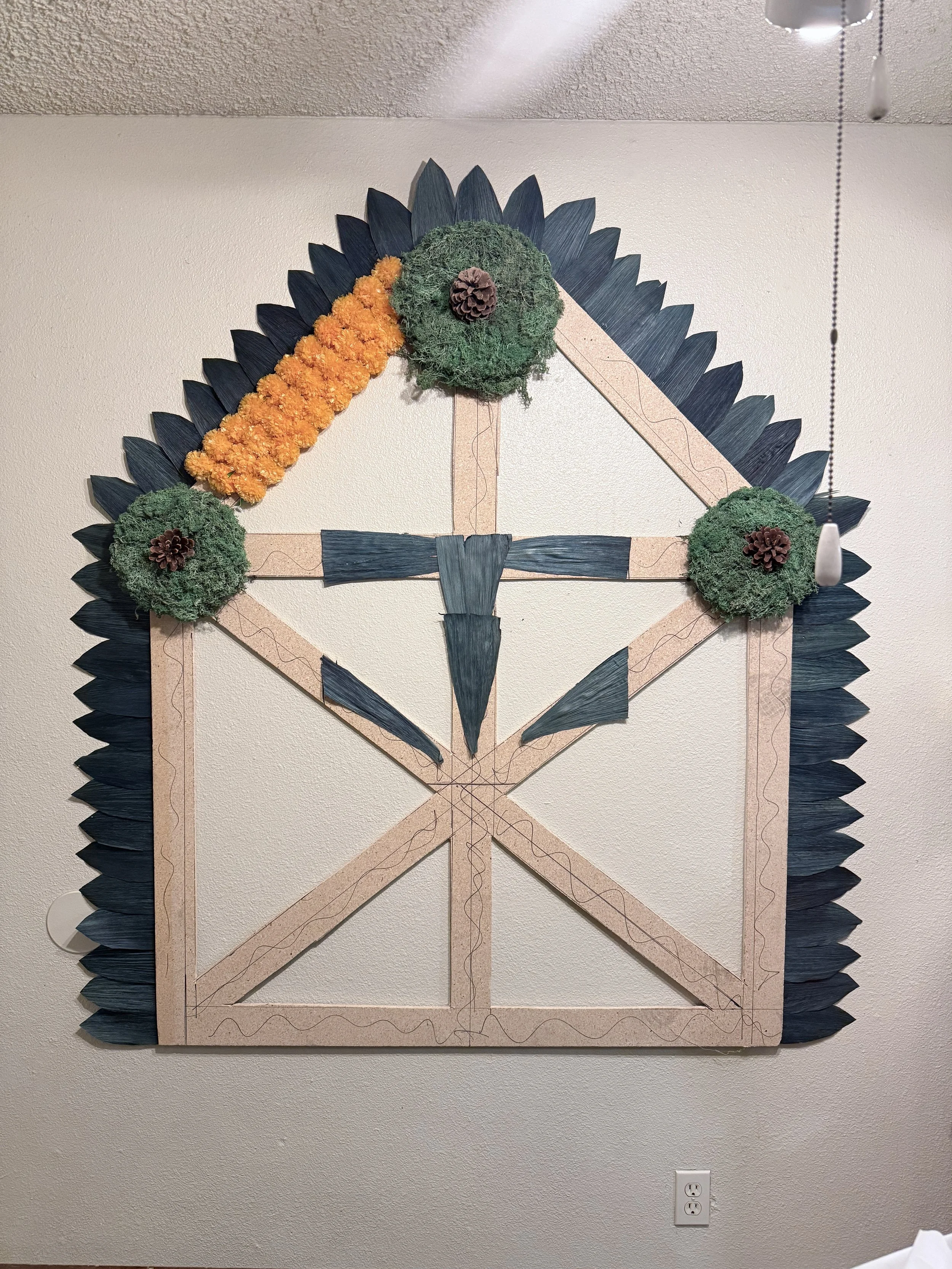

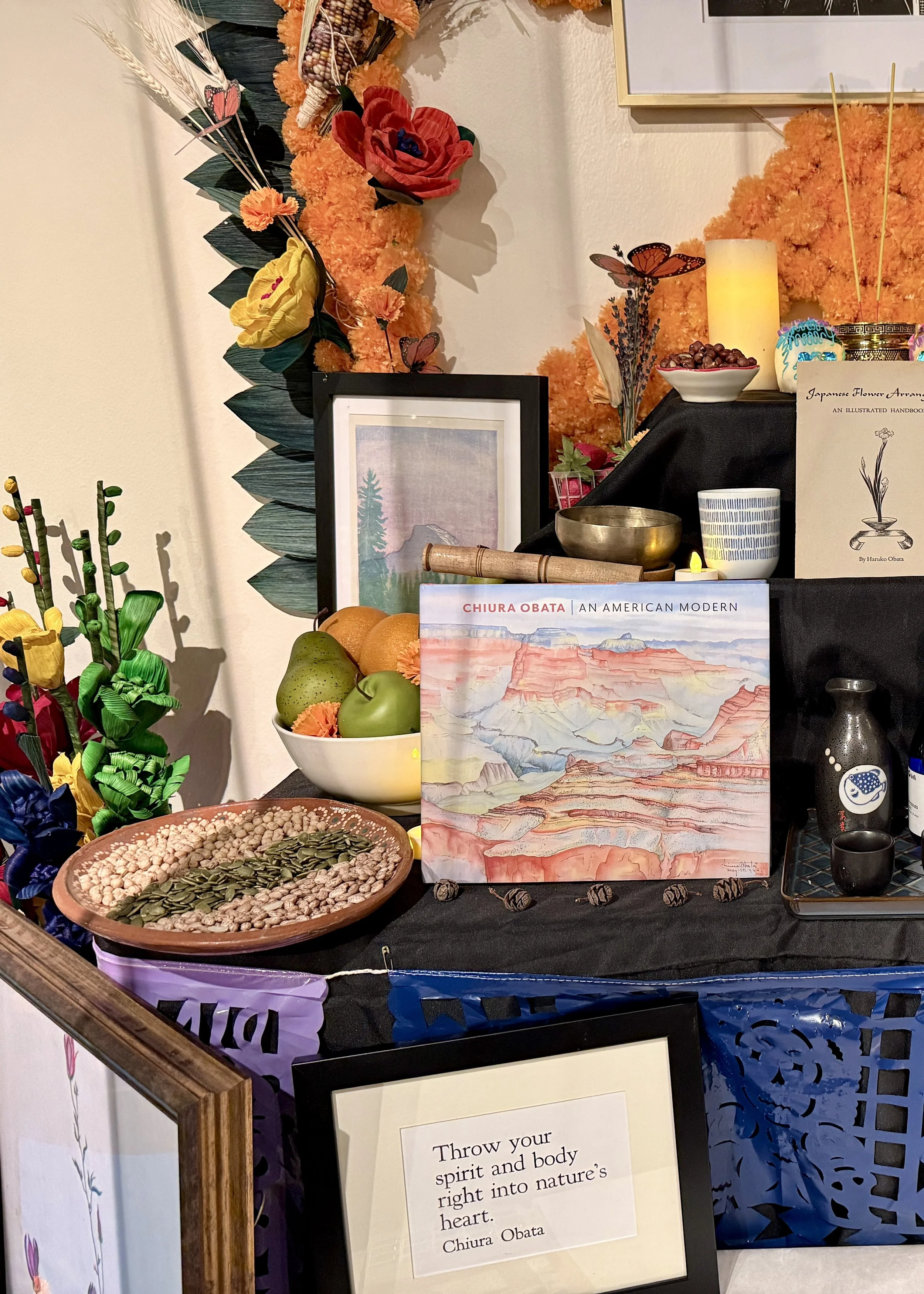

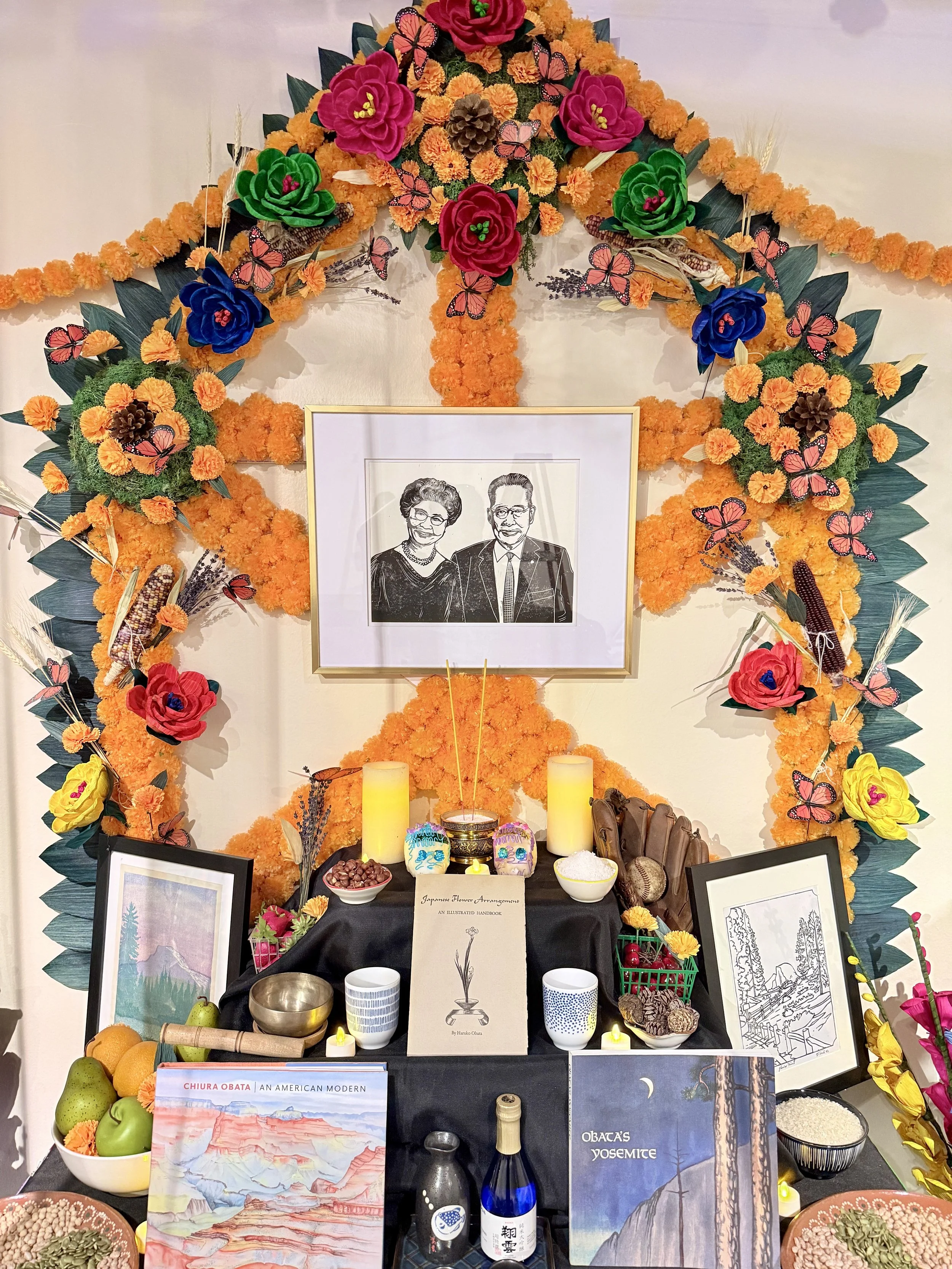

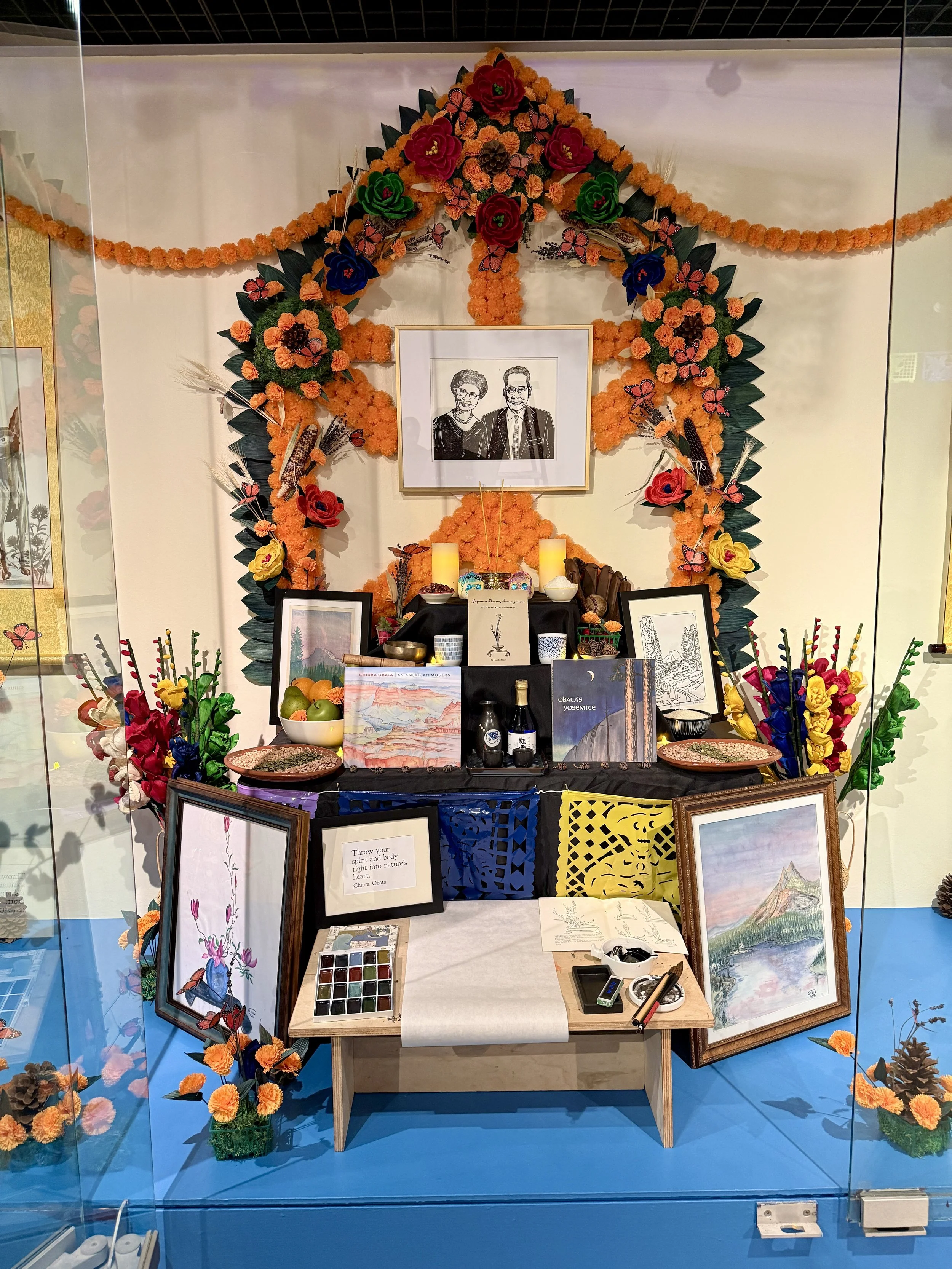

Craft as art

When I began envisioning this altar, I knew I wanted to create something reminiscent of the ofrendas I remember from my childhood in Pátzcuaro, while weaving in Japanese elements throughout. This project became very much a family endeavor. My mother shared her flower-crafting techniques, my brother Iván helped build and reinforce the structure of the altarpiece, and my spouse, Brandon, assisted with foraging pinecones and setting up the display. An ofrenda, above all, is a labor of love created by and for family.

The altar is composed of more than three hundred flowers: some plastic, some natural (dried lavender), and others handcrafted from dyed cornhusks. Three different types of pinecones were foraged: some from the Sierra Nevada, others from the UC Berkeley campus, and a few from a Metasequoia gifted by Kimi Hill. A tree thought to have been extinct since the Miocene but rediscovered after World War II. The pinecones were chosen to represent Obata’s deep love for trees; in much of his work, one can almost always find a tree and often, a pinecone standing as a quiet symbol of endurance and the heavenly and earthly realms.

For the Purépecha people of Michoacán, the monarch butterfly and corn hold deep cultural and spiritual significance. Each fall, as the monarchs migrate from Canada and the United States to the mountains near Pátzcuaro, their arrival coincides with Día de los Muertos and is believed to represent the returning souls of ancestors. The butterfly thus becomes a living symbol of migration, transformation, and the enduring connection between worlds.

Likewise, corn, a sacred plant in mesoamerican cultures, is seen as the sustenance of life, representing both nourishment and cultural continuity. Together, these symbols embody the resilience of the Michoacán region and mirror the immigrant experience: movement across borders, renewal through change, and the deep roots that sustain identity across time and place.

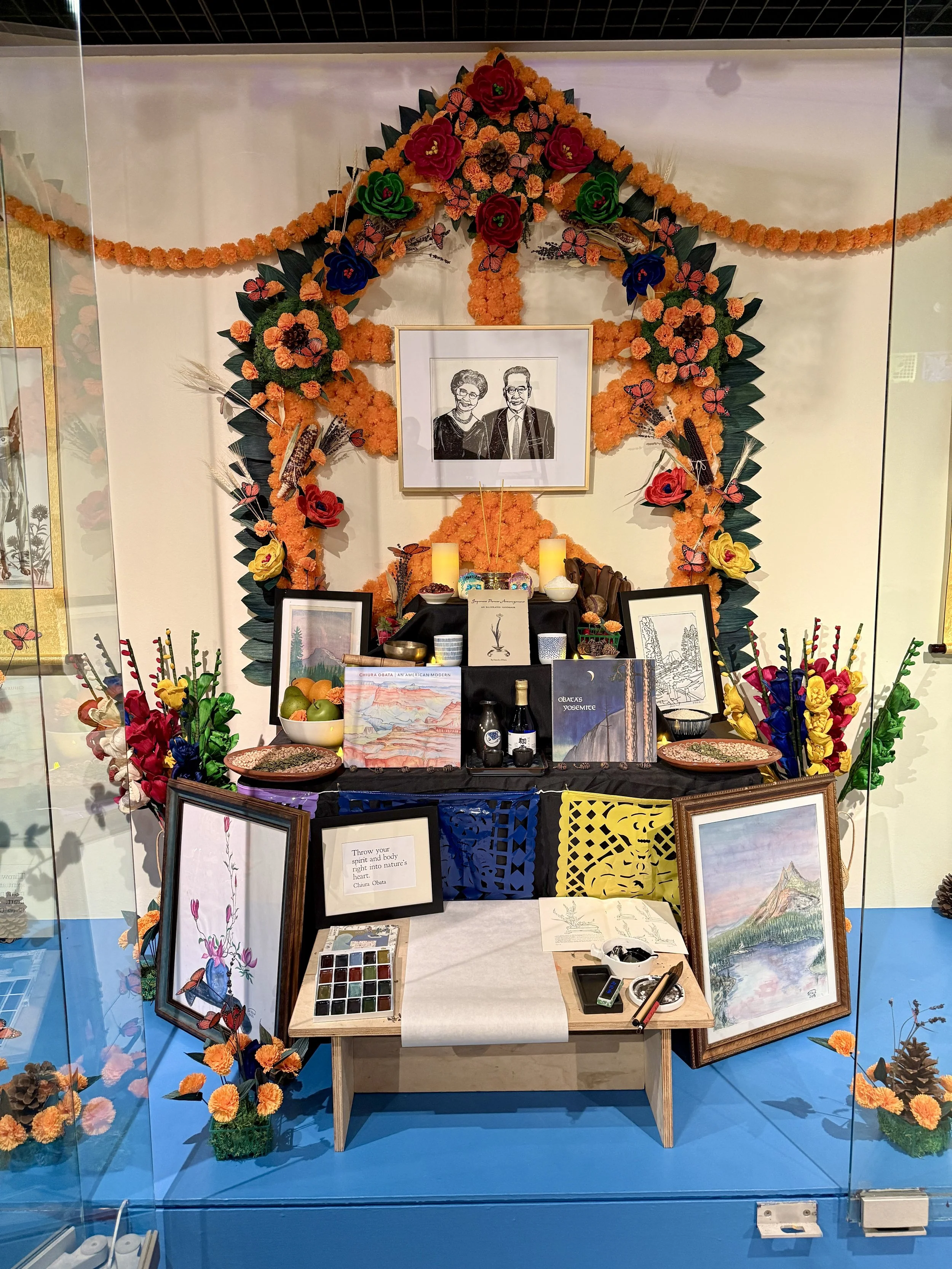

Obon & Dia de los Muertos

The altar was divided into two halves, the left dedicated to Haruko, and the right to Chiura. Throughout the altar are elements commonly found in both Día de los Muertos and Obon altars: offerings of food, candles, incense, and flowers that serve as bridges between the living and the departed. Together, these traditions intertwine honoring the cycle of life, memory, and renewal that transcends borders and cultures.

Chiura Obata

“Throw your spirit and body right into nature's heart.”

Haruko Obata

“The essence of flower arrangement is modeling of natural beauty into art.”

The Artwork

The altar includes seven new pieces

-

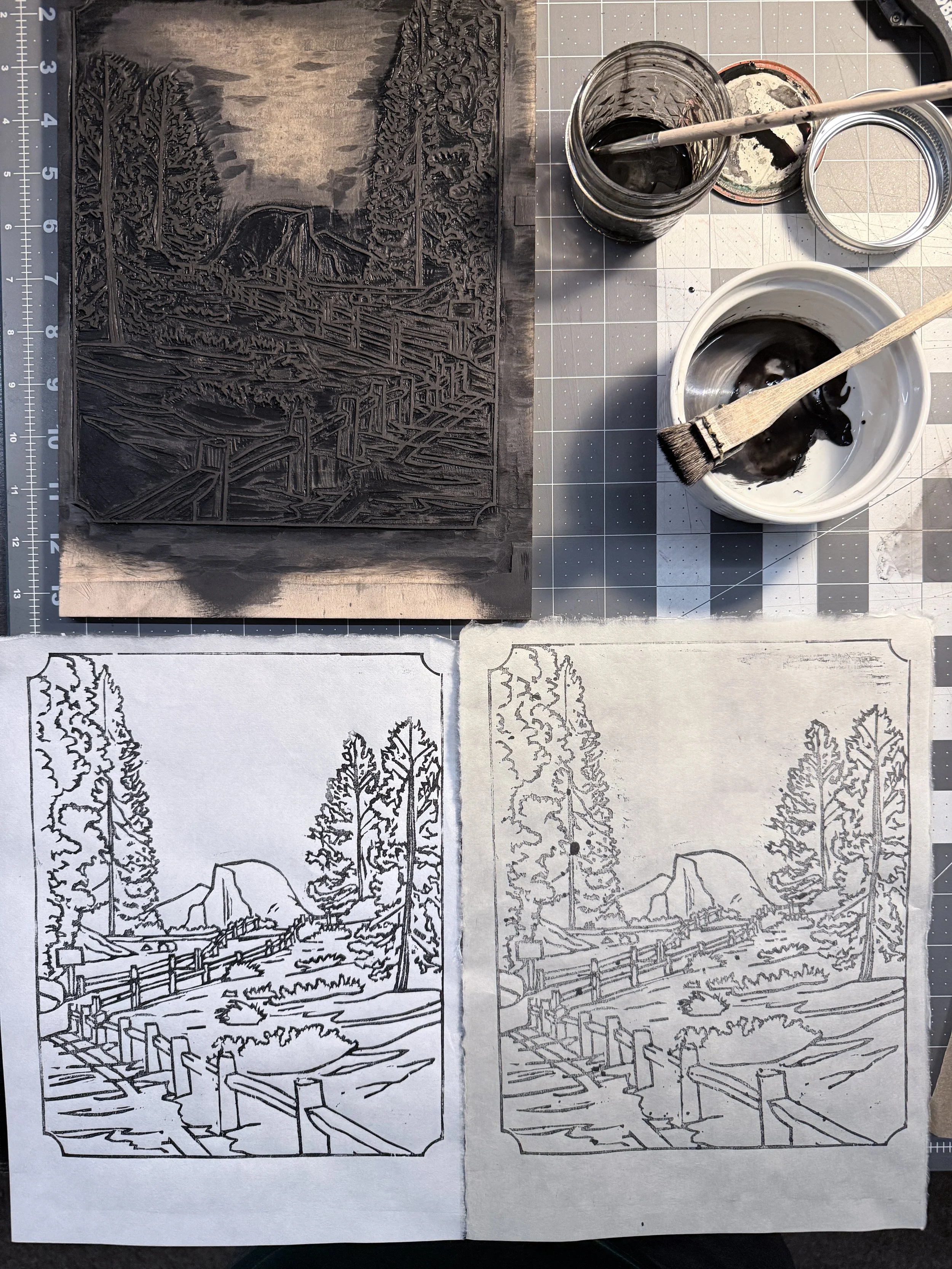

Linocut Awagami Hosho Paper

11×14 in

The central focus of the altar is a double portrait of Mr. & Mrs. Obata.

-

Watercolor on Masa Dosa Paper

16x20 in

Haruko Obata’s mastery of ikebana the Japanese art of flower arrangement and her deep appreciation for balance, grace, and the quiet dialogue between nature and the artist’s hand. The magnolias, symbols of dignity and perseverance, echo Haruko’s own refined strength and creative sensitivity.

-

Watercolor on Awagami Hakuho Select Paper

16x20 in

Chiura Obata’s lifelong devotion to Yosemite and his philosophy of “Great Nature.” These landscapes embody the awe and harmony he sought to capture through his brushwork where human spirit and natural grandeur merge.

-

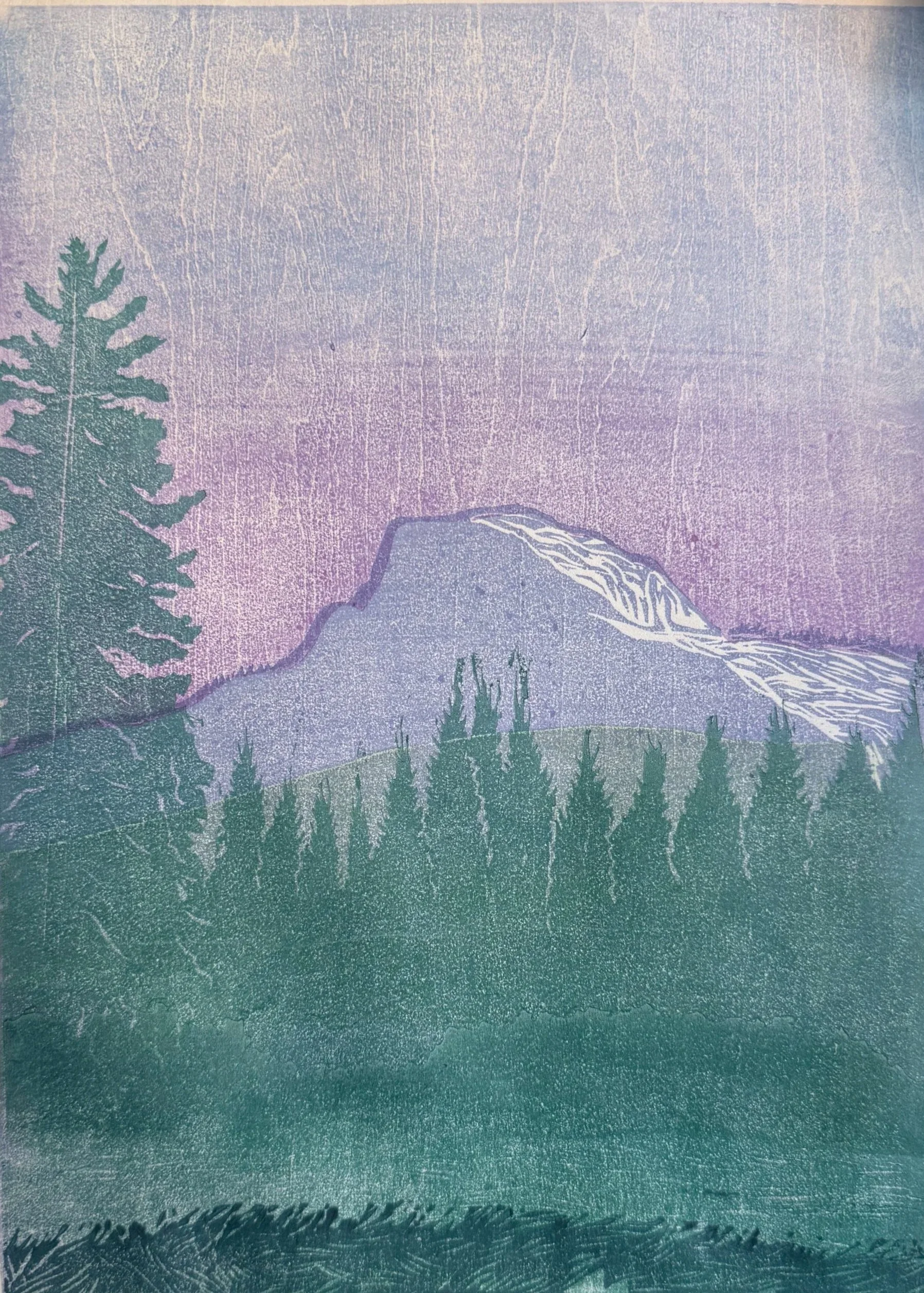

Seven-layer woodcut — Mokuhanga on Awagami Hōsho Paper

9×12 in

The inclusion of this mokuhanga (Japanese woodblock print) within the altar reflects the series of prints created in Japan that were based on Chiura Obata’s Yosemite paintings. Its presence honors Obata’s legacy of blending Japanese printmaking traditions with the awe-inspiring landscapes of California, uniting two worlds through art and nature.

-

Sumi-e on Xuan Paper Scroll

15.5x48 in

The scrolls serve as a cultural bridge, connecting Mexican and Japanese traditions of honoring the dead. The Xoloitzcuintle, a sacred dog in Mexican cosmology, is believed to guide souls to the afterlife. Positioned within the altar, this motif unites the spiritual pathways of Día de los Muertos and Obon, symbolizing the universality of remembrance, love, and the eternal return of the spirit

-

Woodcut - Mokuhanga Awagami Hōsho

8.5×11 in

This view of Glacier Point serves as a reminder of Chiura Obata’s unique artistic perspective. While he often painted Yosemite’s most celebrated landmarks, he approached them from vantage points that were commonly overlooked. Obata had a remarkable ability to find beauty in the quiet, often dismissed corners of the landscape revealing the harmony and spirit of places others might pass by.

-

Sumi-e on Xuan Paper Scroll

15.5x48 in

n this altar, the Xolo serves as a symbolic counterpart to the guardian lion-dogs (Komainu) often seen at the entrances of Japanese temples, which protect sacred spaces and ward off evil. Positioned within the altar, this motif unites the spiritual pathways of Día de los Muertos and Obon, symbolizing the universality of remembrance, love, and the eternal return of the spirit.